by Zine Magubane

Introduction

Sociologists have long complained that politicians and media outlets routinely ignore them. When the stock-markets tank, MSNBC and CNN bring on a slew of economists. When Trump goes on one of his twitter tirades, both psychologists and political scientists are asked to weigh in. Want to know how or why our present moment is so different from all others? Historians stand ready with the answers. But what about sociology?

In theory, sociology could opine on any of these topics. Yet, given the ostensible theoretical orientation of the discipline—the study of "society"—there is no one area within that expansive agglomeration that sociologists can truly call their own. Until now. The popularization of topics such as "unconscious bias," "White privilege," "racial identity," "structural racism" and even the ur-concept, "race relations" itself have finally given sociology its place in both the political and (more importantly) media eco-systems. "Society" broadly defined has never really been the area of inquiry monopolized by sociologists. Although sociologists study many things and the discipline has a surfeit of subfields—environment, medicine, science, art, politics—from the discipline's inception it has monopolized the study of race.

James McKee's Sociology and the Race Problem: The Failure of a Perspective, published in 1993, noted that although anthropology and psychology both contributed to the development of a social scientific study of race relations, "it was only among sociologists that such a study became a full-bodied specialty."1 Many of the concepts and formulations that have now become everyday commonsense as Americans seek to make sense of their current "racialized"2 reality originated in and with the discipline of sociology. And that (as the title of McKee's book suggests) is a problem.

While individual sociologists may revel in their heightened media profile, a marked upswing in Instagram followers, and (if they are lucky) a coveted place for their work on the New York Times bestseller list, overall the result has been to reduce our collective "racial" IQs. Consider, for example, the recent brouhaha surrounding the decision of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American history in Washington D.C. to post an infographic "Aspects and Assumptions of Whiteness in the United States" that was in fact an anti-racist effort aimed to raise awareness about White supremacy.

The graphic, found in the "Whiteness" section of the museum's "Talking About Race" portal, listed 14 categories of "white dominant culture," a term, it explained, it was using in the following sense:

White dominant culture, or whiteness, refers to the ways white people and their traditions, attitudes and ways of life have been normalized over time and are now considered standard practices in the United States. And since white people still hold most of the institutional power in America, we have all internalized aspects of white culture—including people of color.

Included as examples of White culture were: rugged individualism, valorization of the scientific method, the Protestant work ethic, respect for authority, emphasizing work before play, independence and autonomy, and respect for the nuclear family. It bears repeating that conservatives, for many years, have insisted that cultural traits, rather than economic structures, were responsible for racial disparities in income, education, and prison rates (what sociologists blandly call "life chances"). While the infographic is clearly designed to argue that racism, not culture, is the source of inequality, how they categorize "racial culture" hews uncomfortably close to the conservative line.

One such conservative was Daniel Patrick Moynihan (1927-2003), a sociologist turned senator (D-NY). In 1965 Daniel Patrick Moynihan popularized the "culture of poverty" thesis in The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. Placed side by side the Moynihan report and the Smithsonian infographic are inverted mirror images of one another. The infographic lists blind fealty to the strictures of the nuclear family, dominated by a male breadwinner, as one of the characteristic features of "White culture." The Moynihan report, on the other hand, described one of the distinguishing features of Black culture as its "matriarchal" family structure:

Ours is a society which presumes male leadership in private and public affairs. The arrangements of society facilitate such leadership and reward it. A subculture, such as that of the Negro American, in which this is not the pattern, is placed at a distinct disadvantage.3

Both the infographic and the Moynihan report listed commitment to the "work ethic" as a cultural trait that manifested differently in different races. According to the Smithsonian, White culture "values work above play" while Moynihan decried the "low aspirational level" among Black youth. Likewise, both the Museum and Moynihan identified modes of mental processing as race-specific cultural traits. The infographic listed the "Scientific Method" as an aspect of White culture and listed "objective, rational, linear thinking" as component parts thereof. Likewise, Moynihan stated that "a prime index of the disadvantage of Negro youth in the United States is their consistently poor performance on the mental tests that are a standard means of measuring ability and general performance."

Curiously, the infographic drew the ire not of African American pundits (who, if the infographic were taken to its logical conclusion, had a culture that was neither objective nor rational; valued play before work; did not respect authority; rejected the nuclear family; and encouraged children to be dependent) but rather of conservatives, like Donald Trump Jr. The president's son tweeted: "These aren't 'white' values. They're American values that built the world's greatest civilization."

Media conservative Ben Shapiro echoed him: "[It] suggests that all pathways to success—hard work, stable family structure, individual decision making—represent complicity in white supremacy."4 The museum eventually took the graphic down and issued an apology:

The whole idea behind the portal is how do we give tools to people to have these conversations that are vital to moving forward. This was one of those tools. We have found it's not working in the way we intended. We erred in including it.5

My intent in this essay is to defend neither the museum nor its critics. Although they disagreed on whether the infographic was right or wrong, racist or not, their points of agreement interest me more. Crucially, they both agree that "races" have "cultures"—a notion that has now come to pass for commonsense such that we argue about what the cultural traits are but don't argue with the proposition itself. What the museum infographic did, and encouraged others to do as well, was to take a profoundly mistaken notion of "race as culture" that was developed and refined by sociologists working on the "Negro Problem" in the immediate post-Civil War era and repurpose it for White people in the here and now.

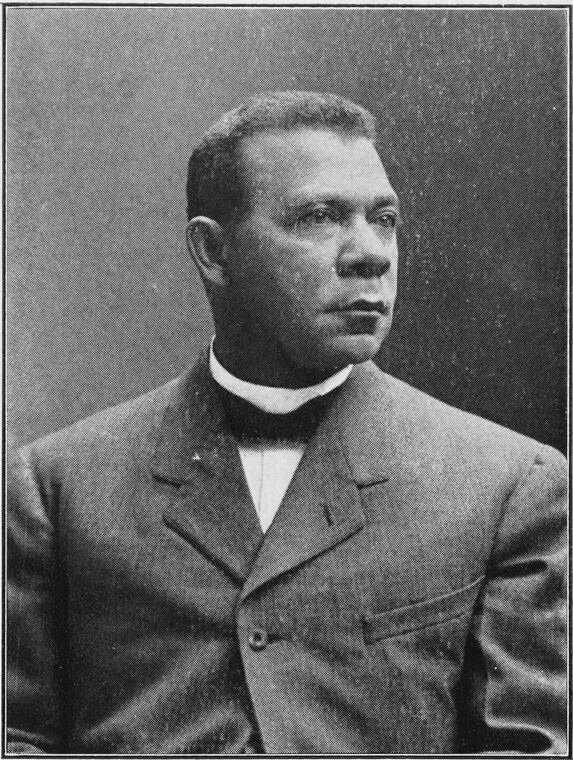

Where did the ideas about race and culture promulgated by not only the Smithsonian infographic but in many other arenas of American life originate? Simply put, these are uniquely American sociological formulations that were designed to "solve" a particular problem at a distinct moment in time so as to benefit a small group of people wielding outsized power. In order to understand what is so wrong about these formulas—how they work to weaken, rather than enhance, understanding—we must go back to the beginning, to the birth of sociology as a discipline in France. We must then retrace its steps across the Atlantic, where it landed on the banks of the Mississippi, wielded as a tool by the slaveholding aristocracy. From there the discipline literally and figuratively was lifted "up from slavery" by Booker T. Washington whose autobiography bears that name. Finally, the discipline came to rest in the hallowed halls of academia—Chicago, Harvard, Columbia, and Yale. As a condition of doing so, however, an awareness of its history was occluded and suppressed. Sociology's object of study shifted. The discipline was, ostensibly, born anew. Yet traces of the old remained—no less powerful for having been willfully submerged and then forgotten.

Because Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, and Max Weber are commonly referred to as the "founding fathers" of sociology, it is little known and less often remembered that the discipline began its life in America as a defense of slavery. The first two books written in English with the word "sociology" in the title were published at the height of the slave holders' power, in 1854. Sociology for the South and Treatise on Sociology: Theoretical and Practical, sought to ground their arguments for the perpetual enslavement of African Americans less in the biological incapacity of the slave and more in a theory of social systems and social relations.

When Booker T. Washington, in the post-Civil War era, began promoting sociology as an applied discipline to "cure" society of the "disease" of racism, sociology shifted focus from defending slavery to managing "the Negro problem." Proper management of "the Negro problem" was defined by Washington and his elite supporters (many of whom were closely tied either to major industrial capitalists based in the North or to plantation agriculture, timber mining, coal mining, or saw mills in the South) as rule by a small, elite class of African Americans over a silent and cooperative mass. Not only would the "Negro masses" be spoken for, but their desires and aspirations would be resolved in ways that did not threaten the rule of private property. The way in which Washington papered over and thus occluded the sharp class differences between persons identified/classified as African-American was to posit an essential cultural similarity that united people across class and silenced any discussion of class conflict within the "Black community."

Robert E. Park, one of the founders of the prestigious "Chicago School" of sociology, began his career ghostwriting for Booker T. Washington. As a result of some well-timed introductions brokered by Washington, he secured a lectureship at the University of Chicago in 1914. While at Chicago, Park developed, refined, and brought to sociological respectability the concept of "Negro culture."

Stanford Lyman, a historian of sociology, once wrote: "To trace the Black man in American sociology is tantamount to tracing the history of American sociology itself."6 The steady growth and attention to what was then called "the Negro Problem" was inextricably intertwined with the development of sociology—the discipline that sought to make valid generalizations about human behavior, social groups, and social progress. The story of how sociology came to be thus positioned—and how it sought to evade and deny its own history in the quest for professional status and prestige—is what motivates this essay.

Sociology and the French Revolution: The Origin of the "Social Group" in Social Thought

It has often been said that sociology is an "invention" of the French Revolution. The rise and development of many of the discipline's central concepts can be traced back to key events in the Revolution, chief among them being the displacement of the King as the source of the nation's sovereignty. Prior to the Revolution the French King ruled by Divine Right. When Louis XIV (1638-1715) declared je suis l'état ("I am the state") he was signaling that he was divinely ordained with the power to absorb, synthesize, embody and express the will of his subjects. There was no dividing line between the state and "society." The King embodied the single superior will that bound together the particular interests in the polity and produced a common good.

The French Revolution, with its ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity, ushered in the ideal of popular sovereignty. When sovereignty came to rest in the people, the notion of the "general will" (first articulated by French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau) moved from an being a metaphysical abstraction to a guiding principle of government. The "generalizing will of the monarch" was replaced by the "collective will of the public."7 "Society"—in the form of individuals with electoral voice—would dictate the doings of the state. As Auguste Comte, the founder of the discipline of sociology explained in 1819, because of the newfound "share which the mass of a nation must take in government," it was necessary to discern the "political will of the nation."8

The collective political will of the public would be made manifest in collectivities that were larger (and superior to) the individual but smaller (and subordinate to) the state—i.e., social groups such as the family, the church, and the neighborhood association. Social groups were crucial in that they facilitated the "vent for social sympathies."9 The social group, rather than "society" thus became Comtean sociology's "central core" and the "nucleus of all its speculation."10 As Robert A. Nisbet explained in an influential article in 1943, "the contribution of sociology to the study of man has lain most significantly in its insistence that men depend upon and are molded by the social groups in which they live."11

The Southern Comteans: Sociology, Slavery, and the American South

Auguste Comte coined the term "sociology" in the 1830s in his five-volume master work, Introduction to Positive Philosophy. He declared that "every sociological analysis supposes three classes of considerations, each more complex than the preceding: the conditions of social existence of the individual, the family, and society." Comte went on to specify that, when he spoke of society, he meant "the whole of the human species, and chiefly, the whole of the white race."12 However, Comte did not believe that people of African descent were permanently and irretrievably outside "society." He had high praise for the people of France's former colony, Haiti, which "had the energy to shake off the iniquitous yoke of slavery." He was even more complimentary towards people living in central Africa who "have never yet been subjected to European influence." He felt that their lack of exposure to the brutality of the West had left them in a better position to receive the wisdom of positivist philosophy:

European pride has looked with contempt on these African tribes, and imagines them destined to hopeless stagnation. But the very fact of having been left to themselves renders them better disposed to receive Positivism, the first system in which their fetishistic faith has been appreciated.13

Comte was also strongly opposed to chattel slavery. He described it as "dreadful," a "righteous horror," and a "factitious anomaly."14 It is somewhat ironic, therefore, that the persons most interested in sociology in general and the work of Comte in particular were slaveholding Americans. These individuals saw sociology as particularly useful for making an argument about the compatibility of slavery with a modern social order. Henry Hughes, author of Treatise on Sociology: Theoretical and Practical,and George Fitzhugh, author of Sociology for the South, were attracted to sociology for a number of distinct and importantly revealing reasons. Hughes borrowed Comte's idea that every effort at societal transformation must start out with a theory before moving to praxis. In his 1824 essay, "Plan of the Scientific Work Necessary for the Reorganization of Society," Comte noted that "any sort of plan of social organization" had two elements. First came the "development of the seminal idea of the plan, that is of the new principle according to which social relations must be coordinated." Second came the "practical" which determined the "mode of distribution of power and the system of administrative institutions."15 Hughes agreed that "conception precedes realization" and that man must have "information before reformation."16 Hughes also liked Comte's focus on social processes such as progress, adaptation, and association as well as on social systems. He opened his text with the following declaration: "The first end of society is the existence of all. Its second end is the progress of all."17

George Fitzhugh, by contrast, was attracted to Comte's thought because he wished to highlight the distance between the social order he wished to protect and the social order that produced a discipline like sociology. For Fitzhugh, sociology was the science of "social afflictions" which described and sought to remedy all of the ills of modern industrial society and the free labor regime that was its bedrock. Thus he opened his text by declaring how much he "did not like to employ the newly-coined word Sociology" and credited chattel slavery for the south's "happy exemption from the social afflictions that originated this philosophy."18 Like Hughes, however, he was interested in a science that purported to be able to deal scientifically with "men's social relations and moral duties" particularly in light of the change from a system of hierarchy and privilege to one of "universal liberty and equality of rights."19

The foregrounding of moral duties (particularly as they related to work) was likely what attracted both men to Comte. Though Comte fiercely opposed slavery and broadly supported the goals of the French Revolution, he nevertheless was also committed to a hierarchically ordered society. He simply wanted a system that wasn't mired in false and retrogressive ideologies of birth, blood and religious doctrine. Fitzhugh and Hughes did want their hierarchal systems to be rooted in notions like blood and divine will. They nevertheless appreciated Comte's emphatic insistence on the need to inculcate proper habits and attitudes towards work when any system of privilege collapsed. Comte firmly believed that if people were to be trusted to live under a system of social order wherein they were no longer subject to force, they had to possess "habits of order, economy, and love of work." If men and women didn't possess those characteristics, they had to be "led to the edge."20

Comte made accepting one's subordinate place in a hierarchical social system and submitting to work an index of a person's moral capacities. This acceptance constitutes the essence of the belief system behind the slogan he is most famous for: Order and Progress. For Comte, Progress meant liberty, the end of feudal social relations, and the opening up of social mobility for men of talent. Order meant respect for property and deference to authority figures, especially bosses:

The people gradually contracted all the habits of love of order and of work, all those habits of foresight and respect for property. ...[P]rogress has been great enough for the people no longer to need to be governed by force. ...[T]he action of government is to be reduced to what is essential to institute a proper coordination of work.21

Hughes echoed Comte when he wrote:

Everybody ought to work. Labor whether of mind or body is a duty. We are morally obliged to contribute to the subsistence and progress of society. The obligation is universal. To consume and not to produce either directly or remotely is wrong. Idleness is a crime. It is unjust. Every class of society has its economic duty.22

From Comte George Fitzhugh borrowed the idea that what distinguished a "society" from merely a horde or an "agglomeration of a certain number of individuals on the same soil" was the people's commitment to "general and combined action."23 Fitzhugh put it even more simply: "Society [is] a band of brothers, working for the common good, instead of a band of cats biting and worrying each other."24 According to this conception of social order, enslaved Africans in the United States were not part of "the people." They contributed nothing to the "general will." Instead, enslaved Africans were wards of the state. Slavery was allegedly the beneficent institution that protected them:

The Negro is improvident. He will not lay up in summer for the wants of winter. He will not accumulate in youth for the exigencies of age. He would become an un-sufferable burden to society. Society has the right to prevent this, and can only do so by subjecting him to domestic slavery.25

Unlike Comte, Hughes excluded people of African descent from the category "the people." He wrote, "The black race ought not to be admitted to co-sovereignty. It is wrong: it is a violation of moral duty." Hughes made the preservation of race "hygiene" the ethical duty of each person. "The preservation and progress of a race, is a moral duty of the races."26 Although Hughes (unlike the sociologists who would follow in his footsteps) wrote very little about the characteristics of people of African descent, he does gesture broadly to the idea that each race group has its own special essence. "Men have not political or economic duties only. They have hygienic duties. Hygiene is both ethnical and ethical; moral duties are coupled to the relation of races. Races must not be wronged. Hygienic progress is a right."27

Like Hughes, Fitzhugh held fast to the idea that each race has its unique essence. Some races are born to be masters and others to be slaves. He described Anglo-Saxons as akin to "the wire grass [that] destroys and takes the place of other grasses."28 However, he rejected the idea of separate creation because it "cut off the negro from human brotherhood and justifies the brutal and miserly in treating him as a vicious brute."29 It was better, he surmised, to think of each race as playing its own unique part and having its own, unique function. If societies were integrated wholes, composed of functionally integrated parts (i.e., social groups), then enslaved Africans had their assigned place as plantation laborers because they were "admirably fitted for farming and too ignorant and dull for any of the finer processes of the mechanic arts." Whites, in turn, found themselves "elevated by the existence of negroes" which gave Whites (especially poor Whites) the opportunity to become "a noble and privileged character."30

This first iteration of American sociological thinking gave Comtean ideas of sociology a distinctly American twist. Only Whites were deemed capable of embodying a "general will" and enslaved Africans were constituted as a people outside and separate from the concept of "the people." And yet, enslaved Africans did have a place in "society"—defined as a group of individuals engaged in purposeful and combined action. What underwrote all of this was the labor relation. Unlike Comte, who embraced the collapse of the feudal regime with its elaborately articulated system of privilege, while nevertheless holding fast to the idea of hierarchy, the Southern Comteans wanted the proto-feudal plantation labor system to go on forever. Their arguments in favor of making slavery a permanent element of American society, rather than invoking a shared general progress, centered around the idea of groups endowed with particular essences being functionally integrated into the social whole.

It is in this notion of "essences" that we can discern the genesis of what later sociologists would call "culture." When Hughes and Fitzhugh wrote, few disputed that race was a "biological" category. The Creator had made each race and endowed it with its own special nature or "essence." Some were born to be bosses, others to be workers. The notion that races have spirits or essences was of signal importance. The "spirit" of each race operated as a mechanism. The spirit of the race drew its members together. The spirit of the race provided the goal to which purposeful and combined action was directed. Through this idea of spirit the Comtean notion of "group," which he applied to civic association, religious sects, and the family, could now be applied to races. Hughes and Fitzhugh transmuted the Comtean idea that men are "molded by the social groups in which they live" into the notion that men are "molded by the racial groups into which they are born."

Booker T. Washington, Robert Park, and the Rise of "Race as Culture" in Sociological Thought

In 1985 John Stanfield first made the bold claim that "Booker T. Washington, through his sponsorship of Robert E. Park, was a founder of the Chicago school." Since then histories of sociology seldom mention that Robert Park spent many years working for Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.31 Tuskegee, an institution with the express purpose of "teaching the Negro to work," exerted a significant impact on the development of Park's sociological imagination. Washington and Park worked together to build a school that, as Park put it, "prepared its pupils for life in a social order where usefulness of some kind was not merely man's title to honor but his only excuse for existence." Together the two men developed the rudiments of ideas about "race" and "culture," or race as culture, that have now, as the Smithsonian infographic illustrates, become commonplace.32 Park's comments about Tuskegee echo Auguste Comte, who maintained that post-Revolution French society needed a way of establishing hierarchy to ensure order. One of the tasks of a science of society, according to Comte, was to provide "supreme direction of education" which he defined as "the whole system of ideas and habits necessary to prepare individuals for the social order in which they are to live, and to adapt each of them, as far as possible, for the particular station he is to fill there."33

When Park became Washington's ghostwriter and publicist in 1905, he wasn't consciously working towards becoming a sociologist. The discipline was barely institutionalized and was taught at only a handful of schools. Sociology was at that time still tightly connected to the "social reform" movement, which included charities and correction, poor relief, prisons and prisoners, and other activities we now associate with the professional occupation of Social Work. Tuskegee existed firmly within that universe. It was oriented around the social control of people deemed to be social problems.

The "Negro Problem" and the Labor Question

The "Negro Problem" was, at that time, one of America's foremost social problems. Many decades after Washington died, Park described his time at Tuskegee as a "prolonged internship" during which he "gained clinical and first-hand knowledge of a first-class social problem."34 From the point of view of the former plantation owners, industrialists, railway barons, and timber mill owners, the "problem" was that they did not have the control over the Black labor force that they had enjoyed under slavery. The Jim Crow social order was at its heart a White elite's attempt to institutionalize and exert economic and social control. The convict leasing system installed a revolving door between the prison and the factory, as African-Americans were routinely jailed for petty offenses like spitting or public drunkenness. Unable to pay the outrageous bond and bail fees, they often found themselves "working off" the sentence (or the money advanced to them for bail) in a sugar mill, on a chain gang, or in the dank recesses of a coal mine. Tuskegee was a vital part of the Jim Crow social order. As Booker T. Washington explained, "We wanted to be careful not to educate our students out of sympathy with agricultural life."35 Washington often quipped that Tuskegee educated students heads, hearts, and minds—meaning that it trained their bodies to do manual labor, trained their minds to aspire to nothing else, and trained their hearts to love occupying their subordinate niche in the social order.

Comte had dealt extensively with the question of how to make formally free people submit to the compulsion of the market. The biggest fear that animated and motivated ante-bellum sociology was the fear that emancipation would lead to the ruin of the plantations because the formerly enslaved would never again submit to labor. As Hughes put it, "The free labor system is different. It is essentially imperfect. ...Fear of want and desire of bettered condition are imperfect implements of order." 36 In the post-bellum era Hughes's worst fears were realized, as the freedmen defined freedom not as the "opportunity" to work for wages and be in the employ of someone else. Rather, they defined freedom as countless other societies before them that had not yet wholly been severed from the independent means of subsistence had done. They defined it as the freedom to till their own piece of ground; the freedom to produce enough food and other staples to meet their subsistence needs; to be free of the compulsion of the market.

Sociological reasoning after the Civil War was concerned even more than antebellum sociology with the question of labor compulsion and labor supply. The shape that the debate took, however, was not nearly so straightforward as it had been in Hughes and Fitzhugh's day. Instead of discussions about balancing labor supply and demand (in favor, always, of the persons making the demand rather than the persons who constituted the supply) gave way to more inchoate discussions of "Negro character" and "race characteristics." It is in this period that we see the Comtean concern with the social group merge with a rather mystical and metaphysical discussion of the "Negro as a social group." A myriad of questions swirled around the issue: What made the "Negro group" a group? Was membership in the group something that was voluntary or assigned? What were the parameters of group membership? Did the group have leaders? If so, to whom did the task of selecting leaders devolve?

The Negro Problem and "Racial" Identification

In the period of plantation slavery, the answers to the questions posed above had been clear—but only because the pre-sociological questions had been completely different. For obvious reasons, we have now come to think of slavery as a "racial system." After all, it was only persons from Africa (and their descendants) who could legally be owned by others. However, the question of assigning each person to a racial category paled in importance next to the preeminent question of the day: who was enslaved and who was free? The condition of enslavement was, we must never forget, a clearly defined legal relationship and a sheaf of legal documents existed documenting who belonged to whom; when and where a person was purchased; who stood to inherit the slave were the owner to die; and who held the mortgage on the slave and thus had the right to "repossess" if bills were past due. The question of the category to which a person belonged—enslaved or free—was usually decided at birth. Enslaved persons (mothers) gave birth to more enslaved persons. Free persons (no matter their "race") gave birth to other free persons. Because of the aforementioned surfeit of legal documents, it was very easy to know to which group (slave or free) a person belonged.

"Fixing" the "race" of a slave did not hold the importance in regulating social relations that it would come to have in the post-bellum period. After all, it was well known by everybody that there were many enslaved persons on Southern plantations who were completely "White" in appearance.37 In the post-bellum period questions of ownership retreated into the background and questions of "racial assignation" or racial "identification" pressed themselves forward. The latter proved much trickier to "fix." Washington observed that "in one part of our country, where the law demands the separation of the races on the railroad trains, I saw at one time a rather amusing instance which showed how difficult it sometimes is to know where the black begins and the white ends."38 Park agreed that "in America today the Negro no longer represents, as in fact he never did, a pure racial type. The mulatto class is already large and is steadily increasing. There is a considerable number of Negro men and a larger number of Negro women in the Negro race who could easily and do occasionally pass for white."39

It was in the post-bellum period that the importance of "fixing" a person's race (we might call the process racial identification)became of paramount importance. The infamous case of Plessy v. Ferguson (which Washington is clearly referencing in the quote above) turned on the question of establishing how to establish "Negro-ness" in the absence of identifying physical characteristics. Plessy's lawyer (and many others) made the point that his "colored blood" was "not discernible" as Plessy was a Creole of Color—a term used to refer to people in New Orleans who traced some of their ancestors to the French, Spanish, and Caribbean settlers who came to Louisiana before it was part of the United States.40 The most obvious impact of the Plessy case was that it established the legal precedent "separate but equal." Henceforth it was legal to discriminate against African-Americans in the provision of public accommodations. The Plessy case had another important ramification, however. It gave the state the right to assign a person to a race. This enshrined the "one drop rule" as legal orthodoxy. By "one drop rule" was meant that having had a single ancestor of African descent was sufficient to assign a person to the category "Colored." The state hereby stepped into the messy arena of assigning races. It had to. As Walter Benn Michaels has wryly observed, "You can't exclude the black people unless you know which ones they are."41

Crucially the Court's opinion stated not only that there were physical differences between White and Black people, but also cited something it called "racial instincts."42 The notion of "racial instincts" played a key role in trying to provide an anchor, in nature, for the Negro "group essence." Even before the notion of biological race came under scientific challenge, the "lived experience" of persons on both sides of the color line called it into question on a daily basis. Not only was it impossible to identify to which race people should be assigned on the basis of their physical characteristics, it was impossible even to determine which physical characteristics of persons were racial. Hair texture, skin color, eye color, nose shape—none of them had the necessary stability. The state, to which the supreme power now fell of identifying persons and placing them into categories, in Plessy asserted the existence of racial instincts which were no less powerful for being invisible to the naked eye. This concept of "racial instincts" was another stop on the road that would eventually lead to the sociological idea of Black and White "culture."

Turning Class into Culture: The "Civilizational Process" and the "Negro World" Within White Society

When Park began working for Washington he had received advanced training in philosophy as well as historical economics. He was very familiar with Comte's work whom he credited with having given sociology "a name, a program, and a place among the sciences."43

According to Comte, the task of sociology was to explain "the great phenomena of the development of the human race...starting from a state which was barely superior to that of societies of apes...to the point it is at today in civilized Europe."44 Park applied Comte's notion of the "civilizational process" to America and argued that African-American people were best understood as a "folk" people that were gradually transitioning to modernity. Park explained:

I was in the unique position of seeing, as it were from the inside, the intricate workings of an important and significant historical process—a process by which, within the wider cultural framework of American national life, a new racial and cultural minority, or as Washington once put it, "a nation within a nation," was visibly emerging, that is taking new form and substance, as the result of a struggle to raise its status.45

Park deliberately described American society as a "cultural framework" rather than a political economy. This framing further authorized depicting African Americans as an isolated "cultural group" within a pluralistic formation of other cultural groups. This prevented examining individuals as members of different class and occupational strata that were differently situated within an evolving industrial and agrarian political economy.

Through his study of Comte Park arrived at the idea that sociology should be seek to understand the "cultural process by which man has been domesticated and human nature formed."46 When Park spoke of the "domestication" of people it was a way of reframing slavery—a system of forced labor for the production of agricultural commodities—into a cultural transformation mechanism. In 1912, at a conference sponsored by Tuskegee Institute, Park presented a paper titled "Education by Cultural Groups." In it he called slavery an "apprenticeship of the younger to the older races."47 He depicted Tuskegee Institute as providing an education, not for placement of persons in a particular position with respect to a political economic structure, but rather as an educational institution best equipped to serve the unique "cultural needs" of a particular group. He went on to call Tuskegee a "cultural entity."48

It was at this 1912 conference that Park met the University of Chicago sociology professor, William I. Thomas, who would help him to secure employment there. The same year that Park joined the University of Chicago faculty as a lecturer he published his first article in sociology's most prestigious journal, The American Journal of Sociology. The article, "Racial Assimilation in Secondary Groups with Particular Reference to the Negro," portrayed slavery as a cultural institution where "racial instincts" and "racial temperament" dictated who did what on the plantation. He argued that the southern plantation was "founded in the different temperaments, habits, and sentiments of the white man and the black." He then went on to assert that the differences within "Negro culture" in the post-bellum period could be attributed to different plantation types:

An outline of the areas in which the different types of plantation existed before the War would furnish the basis for a map showing distinct cultural levels in the Negro population in the South today.49

Both Parks and Washington nevertheless insisted that in the post-bellum period any "cultural differences" were disappearing and a homogenous agglomeration called "Negro culture" was being formed:

Common interests have drawn the black together. ...[there] is a common interest among all the different colors and classes of the race. This sense of solidarity has grown up gradually with the organization of the Negro people. ...Gradually, imperceptibly, within the larger world of the white man, a smaller world, the world of the black man, is silently taking form and shape.50

This way of thinking about and conceptualizing the histories of persons categorized as African or African American bears the imprint of the legacy of Comtean sociology—with all of its shortcomings. It reproduces the logic of the social group conceived of as an organic entity animated by a collective mind and will. It supplies the vehicle for a distinctively American logic of labor discipline and control undergirded by the depiction of African Americans as a "nation within a nation."

"A Nation Within a Nation": The World of Elite Brokerage Politics

Park was also clearly influenced by Comte's ideas about how the "civilizational process" connected to what Comte had called the "progressive course of the human mind."51 One of the main weaknesses of Comte's theory was the way in which it explained (or failed to explain) the connection between the individual and the larger whole—between the individual psyche and the "collective conscience." This failure is likely due to the way in which Comte theorized the "general will" which tracked much too closely to how the French King had been imagined to embody the will of the French people:

The progress of the individual mind is not only an illustration, but an indirect evidence of that of the general mind. The point of departure of the individual and of the race being the same, the phases of the mind of a man correspond to the epochs of the mind of the race.52

The unsatisfactory way in which Comte resolved this problem was to focus on social groups—as though reducing the size of the unit resolved the tension between the mind or will of an individual and the mind or will of a collective. Park, who looked upon Comte favorably as having provided a blueprint for the "scientific" study of culture, imported this epistemological shortcoming into his understanding of what he came to call "the Negro world within the white."53

Park and Washington often spoke of African Americans as a "nation within a nation." This intellectual innovation was not motivated by arcane or lofty philosophical ambitions. Rather, it was part of a political calculus whereby Washington was seeking to portray himself as the "leader" of "his race" and thereby secure his position as the most powerful African American in the arena of elite brokerage politics. Using the metaphor of "nation" to refer to a group of persons classified or identified by race suggested an anti-democratic logic of constituency building antithetical to a more civic oriented politics of "race leadership." The leaders of nations are elected; the leaders of races are not.

Washington often said it was necessary to "cement the friendship of the races."54 Clearly, friendships can only be cemented between individuals. To make "friendship" a group level phenomenon meant establishing agreements between elite individuals—between what Washington called "the best of the Whites and the best of the Blacks." The Southern Sociological Congress played a key rold in this project. Washington, speaking before the Congress in 1914, said:

I want to speak of some special ways in which it seems to me this Congress can promote the welfare of the people of the South. First, it can serve as a medium for direct and candid expression of opinion on the part of the members of both races in regard to matters of common interest. When we consider all that the South has been called upon to do and bear in connection with the readjustment of its economic and social program, the wonder is that so much has been accomplished within so brief a space of time. What we want to be sure of is that progress is in the right direction and is constant and steady.55

When Washington spoke of "matters of common interest," the immediate question that springs to mind should be "of interest to whom"? Who defined the goals of progress? Who was the arbiter of the "right direction"? How can races have "leaders" when no formal (or informal for that matter) mechanism exists to either elevate such leaders to power or depose them?

The way in which a "race leader" like Washington was imagined to operate mirrored the leadership of the French King, Louis XIV, when he declared that he was the state and had the divine power to intuit, embody, synthesize, and express the will of his people. Modern democratic popular sovereignty was meant to supersede such ideas and render them moot. Popular sovereignty relies on the mechanism of elections. People elect leaders to represent them. Washington never stood for formal election to any office. In fact, he frequently preached against it. When he said, for example, in his famed "Atlanta Compromise" address of 1895 that Blacks and Whites should strive to be "separate as the fingers of the hand" in social affairs yet seek to work together for "economic progress," he also depicted popular sovereignty as a dangerous distraction from the business of working and making money:

Ignorant and inexperienced, it is not strange that in the first years of our new life we began at the top instead of at the bottom; that a seat in Congress or the state legislature was more sought than real estate or industrial skill; that the political convention or stump speaking had more attractions than starting a dairy farm or truck garden.56

Washington often said, as he did the day of the Atlanta address, that he had the ability to convey "the sentiment of the masses of [his] race."57 How could he make this claim? Under the Divine Right of Kings, the mechanism which supposedly made it possible for the King to synthesize and then channel the collective will of the French nation was his divine status—the fact that he had, literally, been touched by God. In Washington's world, the mechanism was the "spirit" or "essence" of the race—its culture. The most elite members of any racial group were said to best embody its cultural ideals and to pass them on to others.

Park agreed with Washington that the "Negro middle class," composed of "merchants, plantation owners, and small capitalists," were the mechanism the obviated the need for any kind of mechanism for formal political representation. The middle classes "filled the distance which formerly existed between the masses of the race at the bottom and the small class of educated Negroes at the top, and in this way has contributed to the general diffusion of culture, as well as the solidarity of the race."58

Substituting the Part for the Whole: Tuskegee and the Birth of "Race as Culture"

Much of Park's work at Tuskegee involved traveling throughout the rural South inspecting small schools that were modelled on Tuskegee. His main goal was to vet the schools that northern philanthropists were considering funding or check up on schools that were currently receiving funding. Although Park staked his claim to legitimacy on the fact that his work with Washington had made him intimately connected with the entire spectrum of the African-American experience—from the most humble to the most elite—in actuality he spent most of his time with school teachers, small businessmen and school principals. He admitted as much roughly three decades after leaving Washington's employ and long after Washington was dead:

During those seven winters when I was at Tuskegee I went all over the South. I did not associate to any extent with white folks but I did get pretty thoroughly acquainted with the upper levels of the Negro world, about which southern white people at that time knew very little. On the other hand, I gained very little knowledge, except indirectly, about that nether world of Negro life with which white men, particularly if they grew up on a southern plantation, knew a great deal.59

Despite the fact that Park spent most of his time with just one small segment of persons and was performing a somewhat arcane task, he identified that small segment as somehow representative of the whole.

Washington had used this same technique of substituting the part for the whole and claiming that the experience of one reflected and encapsulated the experience of all in his autobiographical work. As he explained in the opening pages of a book that he wrote with Park's assistance, The Story of the Negro:

Some years ago, in a book called Up From Slavery I tried to tell the story of my own life. While I was at work upon that book the thought frequently occurred to me that nearly all that I was writing about myself might just as well have been written by hundreds of others, who began their life, as I did mine, in slavery. The difficulties I had experienced and the opportunities I had discovered, all that I had learned, felt, and done, others likewise had experienced and others had done. In short, it seemed to me, that what I had put into the book, Up From Slavery, was in a very definite way, an epitome of the history of my race, at least in the early stages of its awakening and in the evolution through which it is now passing.60

Not only was the small, elite segment able to speak for the rest, they were being deputized to lead the masses, whether the masses wanted their leadership or not. After a graduate left Tuskegee, according to Park and Washington, they would "go forth as representatives to improve his community."61 This formulation was not a random intellectual idiosyncrasy. It reflected the fact that Booker T. Washington had a vested interest in substituting the interest of a segment of African Americans—those like him who were connected to the Republican political machine and who were small business owners and teachers—for the interests of the whole. The vast majority of African Americans, stuck on the farms and in the factories, were not from this upper stratum and were not served well by Washington's programs. The political movement to which they were increasingly drawn was populism.

The populist movement opposed rule of the bosses. Populists were against the railway subsidies that allowed northern-based railway conglomerates to avoid paying taxes while heavily taxing the peasant sector. They were against the rule of planter and capitalist interests in the South. They were against the reinvigoration of the plantation, which in turn depended upon non-unionized and hyper-exploited labor. They were against the many draconian laws designed to hinder labor mobility and thus worked to depress wages. They were against the program of the "New South" promulgated by the Republican party which promised that "a community of equal men could be created by allying labor (blacks) and capital to produce material progress and enlightenment."62

Populism's political program better suited the needs of the poor and working classes, Black and White. The populist movement worked on initiatives such as the sub-treasury plan which would cheapen agrarian credit and help to break the back of the crop-lien system. They aimed to change the class character of society by increasing workplace democracy through empowering unions. They sought to break up the large plantations and redistribute the lands to the people who had formerly worked them (the famed "40 acres and a mule"). They aimed to free people from the tyranny of bosses by developing forms of self-sustaining co-operatives that were outside the wage-labor relationship. They sought to confront and eventually break the monopolies of capital, transportation, and marketing. In short, they challenged the idea, articulated forcefully by Washington in the Atlanta Exposition address, that labor and capital could be "friends" and that workers should never let their "grievances overshadow [their] opportunities."63

Although segregation and Jim Crow bore down upon all persons identified as African-American, it did not obviate the fact that people were differently situated within the political economy of post-Civil War America. The solutions proposed by Washington and others who were likewise situated, did not work for all. Simply because racism was a situation persons categorized as African American experienced in common, didn't mean that it gave rise to a common consciousness. Indeed, Washington and Park knew this. Park said that in every large city and small town there were "multitudes of Negroes who live miserably."64 And yet he was comfortable saying that those best equipped to speak for, and express the aspirations of, the whole were what he called the "Negroes of the better class."65 Washington, Park's boss, allowed himself to look upon the efforts of African-American miners to strike for better wages and working conditions with contempt. Strikers, he said, were the work of "professional labor agitators" and men who were "two or three months ahead in their savings" and thus wanted to loaf and goof off. In Washington's opinion, "miners were worse off at the end of a strike."66

Although both Park and Washington liked to invoke the idea of the "Negro masses," they were in fact inventing what it appeared that they were merely describing. In one of his first academic articles, "Negro Home Life and Standards of Living," Park described the many social cleavages amongst persons categorized as "Negro." Although his discussion wasn't at all deep or extensive, he did provide a laundry list of differences such as those that marked rural versus urban or people descended from the small class of "free Negroes" versus those whose ancestors had always been enslaved. He provided scattershot references to those in many different professions and occupations—lawyers, vaudeville stage actors, physicians, teachers, sharecroppers, and may more. He also noted that among the small class of peasant farmers, an even smaller group of Black plantation owners was emerging. With no evidence to support the claim, he then pointed to the "Negro middle class" of "merchants, plantations, and small capitalists" as the vehicle through which a "general diffusion of culture" was passed onto the other classes, thus securing the "solidarity of the race."67

This elision of the distance and factors separating the standpoint of a tiny stratum of elites and something he called "the mass" appears in many different places in Park's work. For example, he claimed that the "great 'Experiment Station' at Tuskegee [was] giving the world a true idea of the Negro's real character."68 The article "Education by Cultural Groups," which Park presented at The International Conference on the Negro hosted by Tuskegee Institute in 1912 is crucially revealing. It purports simply to give evidence on the Negro as a "cultural group." In fact, it is one of Park's first attempts to make the case for seeing "the Negro" as a coherent "cultural group."

In this piece, a scant nine pages in length, Park uses the construction "the Negro masses" or "Negro community" eight times. In a typical passage he describes Tuskegee as a school that existed to "benefit the masses of the people." That benefit was to be secured through the agency of Tuskegee graduates who would go forth and "stimulate and direct the efforts and aspirations of the masses of the people."69 The slippage here between Tuskegee graduates and "the masses" is important. Although Tuskegee was not "elite" in the way Harvard and Yale were, it nevertheless aimed to create a particular kind of elite stratum amongst African Americans. Although it is indeed true that all of the students there were put to hard labor—making bricks, digging trenches, sewing, etc., and many of the students were poor in absolute terms—they were, nevertheless, upwardly mobile compared to the thousands of sharecroppers and plantation workers for whom the school was totally out of reach. Washington described the typical student who showed up at his doorstep in these terms: "Most of the students wanted to get an education because they thought it would enable them to earn more money as school teachers."70

Judith Stein aptly describes the ethos of Tuskegee as both a new theory of education and an "ideology that stemmed from a part of the black petit-bourgeoisie, not the masses."71 Washington had described the typical student as "from the plantation districts, where agriculture in some form or other was the main dependence of the people."72 Stein rounds out this picture by pointing to the fact that, because of this, for most of the people "mobility through education [was] an aspiration possible at best for their children, not themselves."73 The people who made it to Tuskegee were, most likely, those children.

This fact however did not stop either Washington or Park from not only eliding the distinction between elite and mass but also making the former speak for the latter. Park wrote to Washington that "no one can know much about the Negro race, either of its difficulties or its possibilities, until he has become acquainted with the masses of the people as they are in the black belt counties of the South." He went on to describe them as "strong, vigorous, kindly, industrious, simple minded, wholesome, and good as God made them." But both Park and his boss knew that Park's primary interactions were not with the masses. In the same letter Park described to Washington having "talked with white people and colored people" and having "interviewed, where it was convenient to do so, prominent citizens, the trustees of the schools and state and county superintendents."74 This same slippage is apparent in Park's 1941 essay, "Methods of Teaching: Impressions and a Verdict," in which he reflects back on how impactful his experience at Tuskegee had been in forming his sociological worldview. He begins by crediting Tuskegee with having allowed him to make his sociology "empirical and experimental."75 He credits Tuskegee with having become "fixed in the habits, customs, and ideology of a whole people."76 He praises Tuskegee students and teachers for having participated in a "great and significant enterprise, namely the education and elevation of a race."77

What is key here is Booker T. Washington's program of elite brokerage. Again, he describes it in an address before the Southern Sociological Congress in 1914 as one wherein the "best element of the white people" were able to "get acquainted with the most useful and best type of black people in every community."78 The most privileged strata of each group came together to dictate the fate of the masses. It is not wrong to hear echoes here of the French King's once divinely ordained power to synthesize the particular interests of the polity and produce the common good of a pre-Revolutionary era. Washington and Park's elite brokerage, after all, makes strategic use of the "general will" that replaced the king's charismatic authority as it had become mystified through Comtean sociology in the form of the concept of a "group mind." Indeed, it is crucial to see how Washington's brokerage politics became an unacknowledged yet integral part of Park's sociology.

Conclusion: Echoes of the Past in the Present

In May, Joe Biden appeared on the morning radio program, The Breakfast Club, and proclaimed, "If you have a problem figuring out whether you're for me or for Trump, then you ain't Black."79 The logic that undergirded his appearance on the show and the statement was a direct manifestation of the legacy of Washington, brokerage politics, and the conflation of racial identification as classification and racial identification as affiliation. Biden, like Washington before him, tied his political fortunes to conflating the two. Likewise, when rapper Ice Cube put forward his "contract for Black America," it was arrived at without democratic consultation. It was nevertheless given a hearing (however perfunctory) by both Republicans and Democrats. A celebrity was here trading on the legacy of the "race leader," self-appointed and speaking on the behalf of silent (and silenced) "masses." In his own words, Ice Cube demanded that politicians sign the contract if they hoped to get "the Black vote."80 Much like Washington, Ice Cube holds himself up as a gatekeeper who can control the votes of a disenfranchised mass. Finally, in our contemporary colloquial habits of speech, phrases such as: "She is Black but looks White" roll fairly easily off the tongue. To cite one example, the singer Halsey (father African American, mother Irish American) recently told People Magazine:

I'm White passing. I've accepted that about myself and have never tried to control anything about Black culture that is not mine. I look like a white girl but I don't feel like one. I'm a Black woman. It has been weird navigating that. When I was growing up I didn't know if I was supposed to like TLC or Britney.81

I'm fairly certain that neither Halsey, nor Joe Biden, nor Ice Cube has ever heard of, or read a word written by, Robert Park. Few people today have. However, when she asserts that she "looks" White but "feels" Black or when Biden claims that "Black" is not just a census category, but is also indexed by voting for him, or when Ice Cube violates the basic principles of contract—consent by two parties—they are all deploying ideas that Booker T. Washington pioneered as political practice. Park and the many sociologists who followed in his wake have cemented this practice as "common sense."

1 James B. McKee, Sociology and the Race Problem: The Failure of a Perspective (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 1.

2 Long before "racialized" became a buzzword, Barbara Fields provided a pointed critique of the word in her essay "Whiteness, Racism, and Identity" (International Labor and Working Class History 60 [Fall 2001]: 50). She called "racialization" a "rotten plank" which could "bear no weight" because "like most adjectives passing for verbs, 'racialize' does not denote a precise action."

5 https://www.theroot.com/african-american-museum-removes-apologizes-for-whitene-1844456781

6 Stanford Lyman, The Black American in Sociological Thought (New York: Putnam, 1972), p.

7 Ellen Meiksins Wood, "The State and Popular Sovereignty in French Political Thought: A Genealogy of Rousseau's 'General Will'," in History From Below: Studies in Popular Protest and Popular Ideology in Honor of George Rudé, ed. Frederick Krantz (Montreal: Concordia University Press, 1985), 120.

8 Auguste Comte, "General Separation Between Opinions and Desires," in Comte: Early Political Writings, ed. H.S. Jones (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 3.

9 Auguste Comte, A General View of Positivism (New York: Robert Speller & Sons, 1957), 161.

10 Robert A. Nisbet, "The French Revolution and the Rise of Sociology in France," American Journal of Sociology 49 (1943): 156.

11 Nisbet, "French Revolution," 162.

12 Auguste Comte, The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte Volume II, ed. Harriet Martineau (London: George Bell & Sons, 1896), 275.

13 Comte, General View, 436.

14 Auguste Comte, The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte Volume III, ed. Harriet Martineau (London: George Bell & Sons, 1896), 51.

15 Comte, "Plan of Scientific Work," 65.

16 Henry Hughes, Treatise on Sociology: Theoretical and Practical (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1854), 72.

17 Hughes, Treatise, 47.

18 George Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South: The Failure of Free Society (Richmond: A. Morris, 1854), v-vi.

19 Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, 9.

20 Auguste Comte, "The General Character of Modern History," in Comte: Early Political Writings, ed. H.S. Jones (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 36.

21 Comte, "General Character," 37.

22 Hughes, Treatise, 95.

23 Comte, "Plan of Scientific Work," 66.

24 Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, 26.

25 Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, 83.

26 Hughes, Treatise, 238-9.

27 Hughes, Treatise, 239.

28 Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, 31.

29 Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, 37.

30 Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, 147.

31 John Stanfield, Philanthropy and Jim Crow in American Social Science (Westport: Greenwood, 1985), 38. See also Andrew Zimmerman, Alabama in Africa: Booker T. Washington, the German Empire & the Globalization of the New South (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010); Aldon Morris, The Scholar Denied: W.E.B. DuBois and the Birth of American Sociology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016); Stephen Steinberg, Race Relations: A Critique (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007).

32 Robert E. Park, "Tuskegee and Its Mission," The Colored American Magazine 10 (May 1906): 351.

33 Auguste Comte, "Considerations on the Spiritual Power," in Comte: Early Political Writings, ed. H.S. Jones (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 205.

34 Park, "Methods of Teaching," 41.

35 Booker T. Washington, Up From Slavery (New York: Dover, 1995), 61.

36 Hughes, Treatise, 91.

37 Jessie Morgan-Owens, Girl in Black and White: The Story of Mary Mildred Williams and the Abolition Movement (New York: Norton, 2019).

38 Washington, Up From Slavery, 48.

39 Robert E. Park, "Review of Black and White in the Southern States: A Study of the Race Problem in the United States From a South African Point of View," The Journal of Political Economy 24 (1916):305.

40 Charles A. Lofgren, The Plessy Case: A Legal-Historical Interpretation (New York: Oxford, 1987), 175.

41 Walter Benn Michaels, The Trouble With Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality (New York: Henry Holt, 2006), 23.

42 Lofgren, Plessy Case, 4.

43 Robert E. Park, "Sociology and the Social Sciences," The American Journal of Sociology 26 (1921): 401.

44 Auguste Comte, "Philosophical Considerations on the Sciences and Scientists," in Comte: Early Political Writings, ed. H.S. Jones (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 159.

45 Park, "Methods of Teaching," 42.

46 Park, "Sociology and Social Sciences," 411.

47 Robert E. Park, "Education by Cultural Groups," The Southern Workman XLI (June 1912): 370.

48 Park, "Education by Cultural Groups," 576.

49 Robert E. Park, "Racial Assimilation in Secondary Groups With Particular Reference to the Negro," American Journal of Sociology 19 (1914): 613.

50 Park, "Racial Assmiliation," 617.

51 Auguste Comte, The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte, Vol. I, ed.Harriet Martineau (London: George Bell & Sons, 1896), 1.

52 Comte, Positive Philosophy Vol. I, 3.

53 Robert E. Park, "Racial Assimilation in Secondary Groups With Particular Reference to the Negro," American Journal of Sociology 19 (1914): 617.

54 Washington, Up From Slavery, 106.

55 Booker T. Washington, "The Southern Sociological Congress as a Factor for Social Welfare," Battling for Social Betterment: The Southern Sociological Congress (1914), 154.

56 Washington, Up From Slavery, 106.

57 Washington, Up From Slavery, 106.

58 Robert E. Park, "Negro Home Life and Standards of Living," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 49 (1913): 148.

59 Park, "Methods of Teaching," 41, emphasis mine.

60 Booker T. Washington, The Story of the Negro (New York: Doubleday, 1909), 1.

61 Park, "Education by Cultural Groups," 375.

62 Judith Stein, "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others: The Political Economy of Racism in the United States," Science & Society 38 (1974/1975): 430.

63 Washington, Up From Slavery, 107.

64 Park, "Negro Home Life," 156.

65 Park, "Negro Home Life," 160.

66 Washington, Up From Slavery, 33.

67 Robert E. Park, "Negro Home Life and Standards of Living," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 49 (1913): 147.

68 Park, "Tuskegee and Its Mission," 353.

69 Park, "Education by Cultural Groups," 377.

70 Washington, Up From Slavery, 59.

71 Judith Stein, "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others: The Political Economy of Racism in the United States," Science & Society 38 (1974/1975): 443.

72 Washington, Up From Slavery, 61.

73 Stein, "Of Mr. Washington," 443.

74 Letter from Robert Ezra Park to Booker T. Washington (May 29, 1913), in The Booker T. Washington Papers, Volume 12 (1912-1914), ed. Louis R. Harlan and Raymond W. Smock (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982), 190-191.

75 Park, "Methods of Teaching," 45.

76 Park, "Methods of Teaching," 42.

77 Park, "Methods of Teaching," 44.

78 Booker T. Washington, "The Southern Sociological Congress as a Factor for Social Welfare," Battling for Social Betterment: Southern Sociological Congress: Memphis (1914): 156.

79 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/23/us/politics/joe-biden-breakfast-club.html

81 https://people.com/music/halsey-reflects-being-white-passing-biracial-woman/